|

An F-35 jet fighter |

As Japan increases its military might, there’s a slight chance it could become involved in conflict on the Korean peninsula

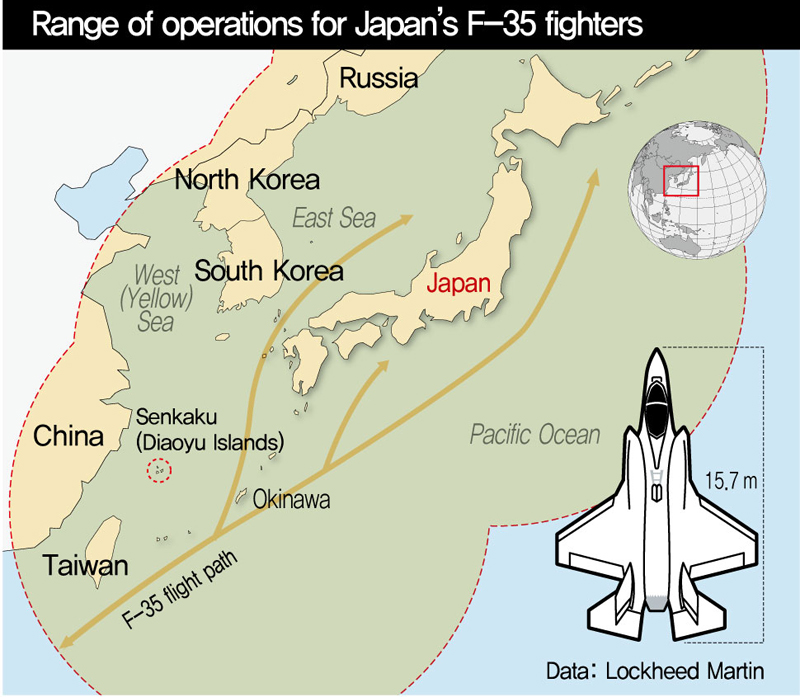

Rep. Keiji Kokuta: The JASDF [Japan Air Self-Defense Force] decided to purchase the top-of-the-line F-35 fighter in Dec. 2011. This aircraft has stealth capabilities that make it extremely difficult for enemy radar to detect it. What is this aircraft’s range of activity?

Defense Minister Gen Nakatani: About 1,100 kilometers.

Kokuta: That means this aircraft is capable of reaching as far as the Korean Peninsula, Russia, and the East China Sea without aerial refueling. Another thing we can’t overlook is the weapons it can be equipped with. What is the JASSM [joint air-to-surface standoff missile]?

Nakatani: That would be the AGM-158, which is a stealth-capable long-range precision-guided surface-to-air missile. Apparently, this missile is currently carried by American F-15 and F-16 fighters and in the future will also be carried by F-35 fighters. However, there are no plans to equip the JASDF’s F-35As with this missile at the present time, and I don‘t know have any detailed information about it.

Kokuta: When you say there aren’t any plans to equip this missile at the present time, it sounds like you’re not completely denying that there are plans to equip it in the future. This weapon has a range of around 370 kilometers. That’s the distance from Tokyo to Nagoya. Isn’t the F-35 a fighter that meets all of the requirements for attacking an enemy base?

Nakatani: While the JASDF currently possesses some of the equipment required for attacking an enemy base, it does not possess the entire range of equipment for carrying out a series of operations. Fielding the F-35 will not change that fact.

Questions by Rep. Kokuta in the special committee of the House of Representatives

It was the afternoon of June 1 during a meeting of a special committee in Japan’s House of Representatives that was set up to review revisions to security legislation intended to allow Japan to exercise the right of collective self-defense.

The last speaker during the day’s review was Rep. Keiji Kokuta, 68, a lawmaker with the Japanese Communist Party, who asked a number of trenchant questions about suspicious remarks that key figures in the Abe administration have made recently about attacking enemy bases.

These questions abruptly added some tension to a meeting that had been on the verge of drawing to an end.

The details of the exchange between Rep. Kokuta and Defense Minister Gen Nakatani goes a long way toward answering a number of questions regarding Japan’s enemy base strike capability, an issue that has provoked unusual interest in South Korea and other countries around Japan.

Japan has repeatedly said that while attacking an enemy base is legally permissible, it is not actually capable of launching such an attack. But Kokuta and Nakatani‘s exchange makes clear that Japan’s strike ability will be strengthened considerably when the Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF) acquires the F-35A (42 fighters are planned).

After Nakatani got flustered by Kokuta’s questions, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe stepped in to restore order. “The main role we are expecting from the F-35 is intercepting enemy fighters,” Abe said, not attacking enemy bases. But doubts about the issue still linger.

There have been various analyses of how the Korean Peninsula would be affected if Japan exercised the right to collective self-defense. The first concern that South Korea had about this issue was whether the Japanese Self-Defense Force (JSDF) would be able to land on the Korean Peninsula without South Korea’s consent.

This concern was provoked by the fact that wartime operational control (OPCON) of South Korean forces is exercised not by the president of South Korea but by the commander of US Forces Korea (USFK). Thus, if US military operations called for Japanese forces to enter South Korean territory, South Korea would not be able to stop it from happening.

This concern was assuaged to some extent by a provision that the Japanese government added to the Major Influencing Event Law bill that it submitted to the Japanese Diet last month. Article 2, clause 4 of the bill states that “measures in foreign territory can only be taken with the consent of the foreign country in question.”

If there were actually a war on the Korean Peninsula, it is impossible to know what decisions the US would make, but the provision that the Japanese government added to the bill does partially clear up South Korea’s concerns.

|

Range of operations for Japan‘s F-35 fighters |

But things took an unusual turn when Nakatani appeared on a morning debate program on Fuji TV on June 17 and expressed the view that Japan’s right to collective self-defense enabled it to attack “enemy bases,” referring to North Korean missile bases. Since this means that Japan could carry out a strike on North Korean missile bases if the North attacked the US - even without attacking Japan directly - this caused a considerable stir even inside Japan.

The ongoing furor in Japan about attacking enemy bases is also creating a headache for South Korea, which must alleviate the threat posed by North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missiles while also pursuing stability in Northeast Asia.

This explains remarks made by South Korean Defense Minister Han Min-koo when he met Nakatani in Singapore on May 30, the first bilateral conference of South Korean and Japanese defense ministers to take place in four years.

During the conference, Han made clear to Nakatani that, since the South Korean constitution claims North Korea as its territory, Japan would have to consult with South Korea before attacking a North Korea base. Nakatani reportedly avoided a direct response and suggested discussing the question later.

During a recent interview with the Hankyoreh, a former Japanese defense minister said that, while he understood South Korea’s concerns, North Korea was undeniably a member of the United Nations.

There are two points on which the recent discussion about attacking enemy bases in Japan differs fundamentally from discussions that have taken place in Japan in past decades. The first point is what the objective of such an attack would be.

Previous discussion in Japan about carrying out strikes on enemy bases has always concerned “individual self-defense,” which presumed a situation in which Japan had been attacked by an enemy state.

The reason that this has been a hot-button issue in Japan’s security policy is because it results in a basic contradiction with the principle of exclusive defense that underpins Japan’s defense policy.

Exclusive defense refers to a passive strategy of defense according to which Japan would only resort to force when attacked by an enemy.

But following this principle to the letter would create a security dilemma for Japan, since it would prevent the country from making a preemptive strike even when it is 99.9% certain that an enemy will launch a missile attack.

Ambiguous changes to the text of the US-Japanese Defense Guidelines |

Japanese Communist Party lawmaker Rep. Keiji Kokuta during a June 4 interview with the Hankyoreh. (by Gil Yun-hyung, Tokyo correspondent) |

Former Japanese Prime Minister Ichiro Hatoyama (1883-1959) voiced his opinion on this question during a cabinet meeting in the House of Representatives in 1956.

“Suppose that Japan was in danger of an imminent and unjust attack and that guided missiles aimed at Japanese territory were to be the method of that attack. In such a case, it seems implausible that our constitution would have us wait meekly for annihilation. Legally speaking, one must conclude that carrying out a guided missile strike on these bases in order to prevent such an attack would fall within the scope of self-defense,” Hatoyama said.

The view that Japan cannot “wait meekly for annihilation” was upheld as an established tenet of the Japanese government in responses to the Diet by previous heads of Japan’s Defense Agency (now Defense Ministry) Shigejiro Ino (1901-1981) in 1959 and Hosei Norota, 85, in 1999. At the same time, Japan has maintained the ambiguous position that its ability to attack enemy bases is strictly legal in nature and that Japan does not actually possess the military capability to make such an attack.

However, in more recent discussion of this issue, the Japanese government has substantially relaxed the conditions under which it could carry out a strike on an enemy base. Even without being directly attacked, Japan would be legally permitted to attack a North Korean missile base, provided that the “three new conditions” for exercising its right to collective self-defense are satisfied, it now says.

The second change is that, in contrast with the hypothetical situations that the Japanese government has been emphasizing, the country has in large part acquired the capability to attack an enemy base.

The most recent steps taken in the discourse about attacking enemy bases were policy recommendations for revising defense policy that Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) made public in June 2013.

In the recommendations, the LPD said, “A decision should be made quickly about whether the JSDF should acquire the capability of attacking enemy bases - a capability that is considered legally permissible - taking into consideration the development and deployment of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles in neighboring countries [that is, North Korea].”

This recommendation was included in the outline of Japan’s defense plans that were announced in Dec. 2013 in the form of a provision that stated, “Necessary measures will be taken after exploring the capability of responding during the launch phase of a ballistic missile.”

At the same time, Japan was negotiating behind the scenes with the US to allow the JSDF future exercise of enemy base strike capabilities as part of the revision of their defense cooperation guidelines, which began in Oct. 2013. A Reuters article from Oct. 2014 quoted sources as saying the Japanese Defense Ministry and US Defense Department were conducting research and discussions at the officer level on what capabilities the JSDF would possess and their possibilities. The result was a change in the guidelines’ wording on enemy base strikes. While the original version stated that the US would “consider, as necessary, the use of forces providing additional strike power,” the version after revision in late April said the JSDF and US would “maintain an effective posture to defend against ballistic missile attacks heading for Japan” in the event of “an indication of a ballistic missile attack.” While the 1997 revision made it clear that the US would be in charge of striking enemy bases, the wording in the new guidelines is vague on the question of who would carry out such a strike.

What are Japan’s enemy base strike capabilities at the moment? While appearing before Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee in the House of Councilors in March 2003, then-Defense Minister Takemasa Moriya, 70, listed a number of capabilities needed for such a strike, including the ability to destroy enemy anti-aircraft radar, low-altitude aircraft penetration, and air-to-service guided or cruise missiles. This, in turn, would require satellites and other intelligence assets to specific which bases to strike, fighters for actual combat deployment, air-to-surface guided missiles for those fighters, tankers to support the fighters on long-distance flights, and electronic warfare aircraft to disrupt radar and interceptor activity at enemy sites, as well as Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) to control everything.

In terms of fighters, the Japan Air Self Defense Force (JASDF) already has a laser-guided joint direct attack munition (JSDM) kit on its F-2. The F-2 also participated in actual firing drills as part of joint exercises with the US and Australia on Guam in Feb. 2014. This capability is expected to develop further once the JASSM is introduced on the F-35. Japan is also acquiring the KC-767 tankers and E-767 AWACS needed for its operations.

This explains why Nakatani offered “the electronic warfare aircraft used to disrupt and neutralize other countries’ anti-aircraft radar” after repeated questioning from Kokuta on the JSDF’s current equipment inadequacies. The information so far suggests that Japan’s enemy base strike capabilities are now at around 80-90% - and that it could carry out a strike against North Korean bases now in a joint operation with the US.

Why did Japan turn down the US’s request for cooperation in bombing Yongbyon? The situation leaves much for Seoul to consider. The chances of the sort of scenario currently being discussed in Japan - North Korea attacking the US, and Japan carrying out a retaliatory strike on a North Korean missile base - are virtually nil. But there is a chance of a JSDF with a greater military role and capabilities influencing future US military decisions regarding North Korea.

Indeed, something similar happened during the first North Korean nuclear crisis in 1993 when the US was considering a surgical strike against Yongbyon, an area in North Korea with a large concentration of nuclear facilities. The US requested some 1,500 forms of support from Japan, including weapons and ammunition, defense of its warships, and use of civilian air and seaports. Tokyo ended up denying the request, citing Article 9 of the Constitution. The US ultimately decided against military action, and the crisis ended in Oct. 1994 with the Agreed Framework in Geneva. It’s a decision that might have turned out differently if the JSDF had had the capability to strike enemy bases and a commitment to using it.

“The US is a country that carries out preemptive strikes, which means that it could be exposed to counterstrikes from the countries it strikes,” Kokuta said in a June 4 interview the Hankyoreh. “The Abe administration’s reasoning, which is that the JSDF could strike enemy bases on behalf of the US when the US is under attack, is extremely dangerous.”

Kokuta went on to stress Japan’s need to “contribute to preventing armed conflict in East Asia before the fact with the spirit of the Peace Constitution.”

“The Abe administration is mistaken to consider only helping the US instead of thinking about South Korea, which stands to suffer the most from an incident on the Korean Peninsula,” he said.

By Gil Yun-hyung, Tokyo correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_northkorea/696809.html